Observability in the Quantum Age

Quantum Internet and quantum networks are slated to play an important role in the future of cloud and distributed computing by enabling a new class of networked applications that are impossible to be implemented using solely classical communication.

In this blog post, we take a look into how traditional observability paradigms such as logs, metrics, and traces can be of use to applications powered by quantum networks. While I have always been interested in the overarching theme of observability in the context of quantum applications, my interest piqued with the publication of QNodeOS[1], an operating system specially designed for enabling quantum networking application by enabling entanglement between two distributed quantum nodes.

You can also read this blog post in its original pdf format here.

What is a Quantum Networked Application?

Quantum networked applications are applications that include multiple nodes communicating over both classical channels as well as quantum channels to perform joint computation. These applications have a mix of classical and quantum executions with continuing interaction between them. This is in stark contrast to quantum computation applications, where one quantum program can be executed in a single batch, without the need to keep quantum states live while waiting for input from other parts of the execution.

Common examples of such applications include Quantum Blind Computation, Delegated Quantum Computation, Quantum Key Distribution, among others.

The Need for Visibility

While quantum networked applications remain in its nascency, developers deeply care about the performance and efficacy of these applications. This need will only be further exacerbated in a true realization of a quantum internet, where the number of nodes communicating would be far greater than just two. Thus, the key requirement for effectively doing performance analysis is to have visibility into the internals of the system and to effectively track the execution across component boundaries.

Challenges

However, gaining visibility in quantum network applications is challenging for many reasons.

- Heterogeneous Applications: these applications are inherently heterogeneous. They are composed of mixed classical and quantum tasks that depend on each other in different ways and often require both classical communication as well as quantum communication performed by dedicated quantum processors and networking units. Thus, we need to track observability not only across network boundaries but also across processor boundaries.

- Non-deterministic Nature: these applications are probabilistic and non-deterministic. The success of the application is often highly dependent on the quality and the fidelity of the entangled states generated. Thus, these applications may require many different executions to gain a meaningful result. As a result, more specialized metrics need to be calculated and tracked on a per-application basis.

- Multiple Sources of Errors: there are a lot of sources of error that can degrade the performance of the system. These may be decoherence errors that cause the quantum state to decohere or collapse as well as errors in application of quantum gates or errors in performing measurements. Thus, the different sources must be accounted for and tracked during the execution which requires obtaining deep low-level visibility.

- High Resource Cost: gaining insight into the quantum states is a difficult and resource consuming process. For example, performing quantum state tomography to measure state fidelity for even a two-qubit state requires performing measurements with different settings to get the full probability density matrix of the state. Thus, we may need to redesign observability techniques to make them more efficiently applicable for quantum networked systems.

Observability: A First Class Citizen

We propose that to enable performance analysis of quantum networked applications, observability must be treated as a first class citizen in the design and implementations of operating systems enabling quantum networked applications.

To overcome the challenges, we need to design dedicated observability units that can track the execution across heterogeneous components and collect relevant metrics associated with the applications. We present our vision of native observability support in quantum networked applications within the context of the design of QNodeOS, the first functional general purpose operating system designed for quantum network applications. Here is our proposed augmented version of QNodeOS.

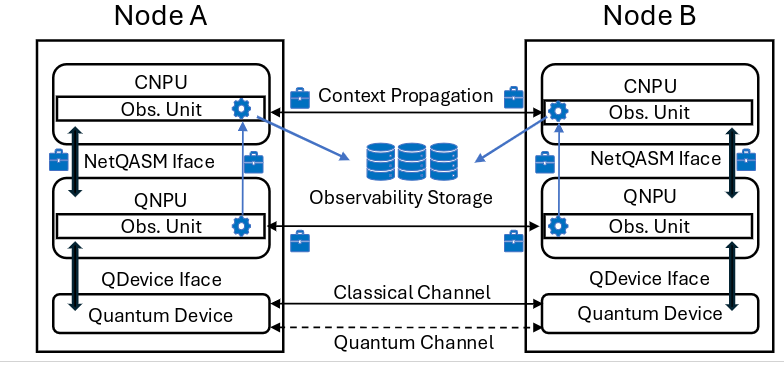

The original QNodeOS design consists of three parts, (i) a Classical Network Processing Unit (CNPU) that handles the execution of the classical part of the user program, (ii) a Quantum Network Processing Unit (QNPU) that executes the quantum part of the user program and manages the underlying resources provided by the quantum device - namely entanglement and qubits, and (iii) a quantum device that provides the quantum resources. We augment the design by modifying the CNPU and QNPU with dedicated observability units that are responsible for providing the three pillars of observability.

Metrics

For quantum network systems, there are a variety of possible metrics developers might need to track. There are two different classes of metrics that need to be measured and monitored - (i) classical metrics, and (ii) quantum metrics.

Classical metrics represent the class of metrics that can be measured using classical techniques and do not require any quantum measurements. Common examples of these metrics include end-to-end latency, server throughput, resource utilization, and power usage. Diagnosing issues requires collecting classical metrics about the quantum aspects of the system. For latency, the developers might additionally want to measure the latency (or waiting time) for generating 1 entangled pair of qubits. For throughput, possible measures include throughput of the number of qubits generated by a quantum device, throughput for the number of entangled pairs generated per second, throughput of the total number of successful entanglement swapping (or teleportation) attempts. For utilization, a sensible metric might be the number of physical qubits utilized per second or the number of logical qubits utilized per second. Utilization metrics might also include metrics about the link utilization of the classical and quantum communication channels between two neighboring nodes. These metrics would need to be tracked by both the CNPU and QNPU.

Quantum metrics are metrics pertaining to the quantum state and require quantum solutions. For example, the most popular example of a quantum metric is fidelity. In a quantum network application, a developer might want to track different fidelity metrics. Fidelity metrics could include the fidelity of the initial states, fidelity of the entangled states, or fidelity of the final computation result. Other quantum metrics include metrics that measure the quality of the entanglement. For example, entanglement entropy measures the quality of the entanglement of a pure state. Some quantum applications even have pre-requisites on the quality of entanglement before execution can happen. For example, the E91 protocol for entanglement-based quantum key distribution requires that the prepared entangled state be a state such that it violates the CHSH inequality. As not all entangled states violate the inequality, it becomes imperative that the quality of the entanglement must be measured. These metrics would need to be tracked by the QNPU.

A key difference between classical and quantum metrics is that quantum metrics are often second order metrics. This is because, to calculate a single value for these metrics, we require multiple measurements, sometimes in the order of thousands, as is the case when using quantum tomography for calculating the fidelity of the entangled state. Thus, we also want to track metrics about these quantum metrics, such as number of measurements per calculation of the metric and resources spent calculating the metric. Moreover, we might need to use sampling strategies to overcome the high resource requirements of measuring quantum metrics.

Tracking Execution

Traces: Traditionally, traces track the execution of a request through the different components of the system. In classic settings, tracing requires propagating a request-specific context across the various component boundaries often demarcated by individual deployment units. However, for quantum network systems, we are operating in a heterogeneous setting with two different processor components providing different capabilities. Thus,to obtain complete executions, we need to now propagate the execution context across both the processor boundaries in addition to the network boundaries to get a full picture of the execution of the system.

To correctly provide tracing capabilities, we propose modifying the CNPU and QNPU design in two ways. First, the CNPU of one node must propagate the context to the CNPU of the other node to establish context propagation over the classical communication channel between the two CNPUs. Second, the execution context must be propagated through the CNPU-QNPU channel which can then further be propagated and attached to the communication with the QNPU of a neighboring node. Propagating the context into the QNPU allows attaching information about the local quantum execution to the trace of the application as well as ensuring that all possible entanglement generation requests and communication with neighboring nodes is correctly attributed to the application. This context propagation is important, as it allows us to correctly attribute usage of quantum resources for different applications especially if there are multiple applications executing over the quantum network at the same time.

Logs: Traditionally, logs capture discrete events within the system. For quantum network systems, there are two distinct sources of events that the user might want to capture – (i) events from CNPU, i.e., the execution of the classical part of the program, and (ii) events from QNPU, i.e., the execution of the quantum part of the program. However, not all events in the two processor units might be specific to a given user program or application. Some of them might simply be housekeeping events for the specific processing unit. Thus, both types of events need to be tracked as well as easily differentiated.

Call-to-Action

The lack of visibility into the performance and execution of quantum applications has the potential to completely block the quantum internet revolution. We believe we have only scratched the surface of the power that observability techniques can provide in the design and maintenance of quantum network systems. We argue that the quantum systems community should work together in developing solutions and techniques that can truly unleash the full power of observability and help in the fulfillment of the immense promise of quantum internet.

References

- Donne CD, Iuliano M, van der Vecht B, Ferreira GM, Jirovská H, van der Steenhoven T, Dahlberg A, Skrzypczyk M, Fioretto D, Teller M, Filippov P. Design and demonstration of an operating system for executing applications on quantum network nodes. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.18306. 2024 Jul 25.